https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2015/06/steven-a-cohen-pet-pig.html?gtm=top>m=bottom

First, you might be wondering, what is scarcity mindset?

When you are living in a scarcity mindest, you believe that there will never be enough [1]. So you hoard.

You hoard power, money, ideas.

VC is living in a scarcity mindset because it has become addicted to hoarding despite operating in an ecosystem of abundance. There is more capital and more entrepreneurs than ever and yet what we’ve seen is that funds have raised more money, hired fewer people and forced more money into fewer companies.

Something has to change.

But before we get into what should change, let’s get into how we got here.

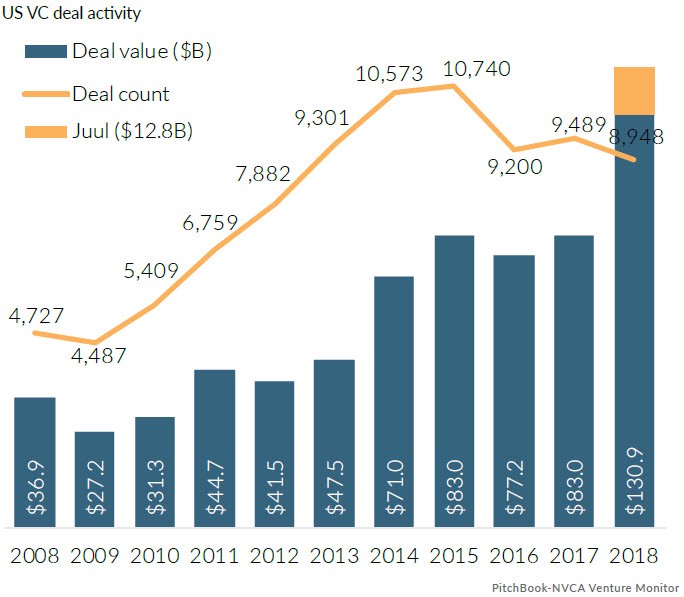

The VC Industry has grown significantly over the last 10 years

VC investing reached an all-time high last year. $130.9 billion was invested into US-based startups.

That is more than the entire GDP of Ukraine, Morocco or Ecuador.

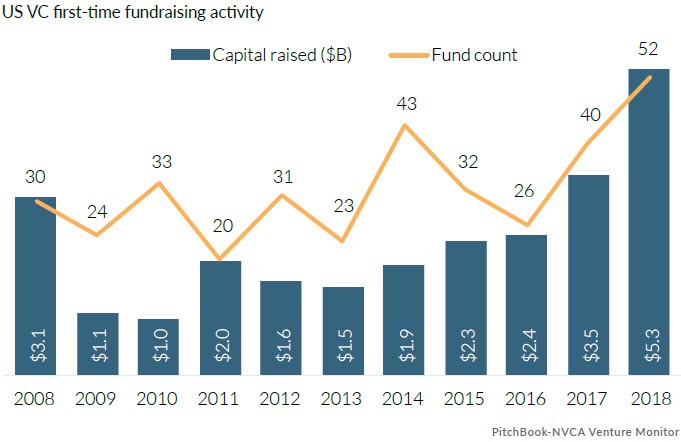

Plus there were more firms created last year than ever before over the last 10 years.

But more money is chasing fewer deals 🤔

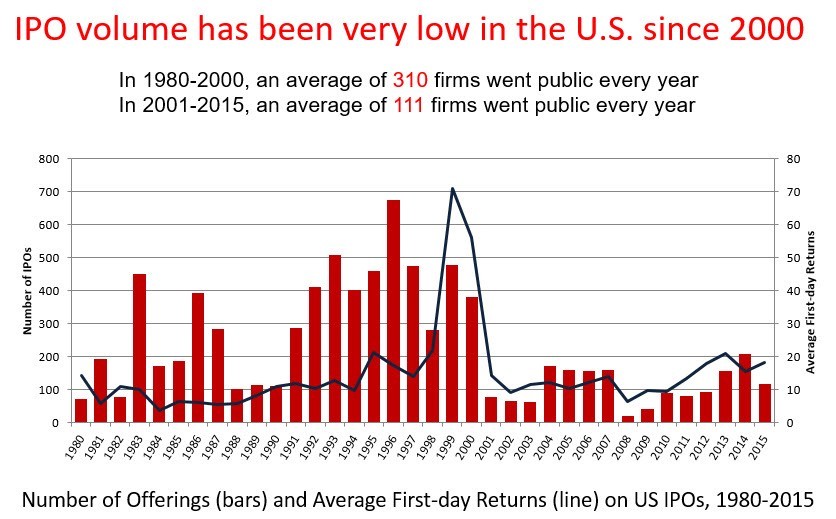

More money is chasing fewer deals and as a result, fewer deals are able to IPO.

The decreasing number of IPOs can be due to a number of factors. One of them is that VCs believe that fewer deals are great and “deserve to IPO”. I think this is a misnomer and self-fulling prophecy because if all VCs think that only a few deals are great, then only a few deals will be great. Luckily there is a growing trend of voices who don’t believe this — like Greenspring Associates who recently wrote that: “the market is expansive and filled with opportunities, when approached with an open mind.” [2]

Another, more tactical factor is that IPOs are expensive and large banks only want to do the biggest ones with the biggest market cap because these have the most potential to impact their bottom line.

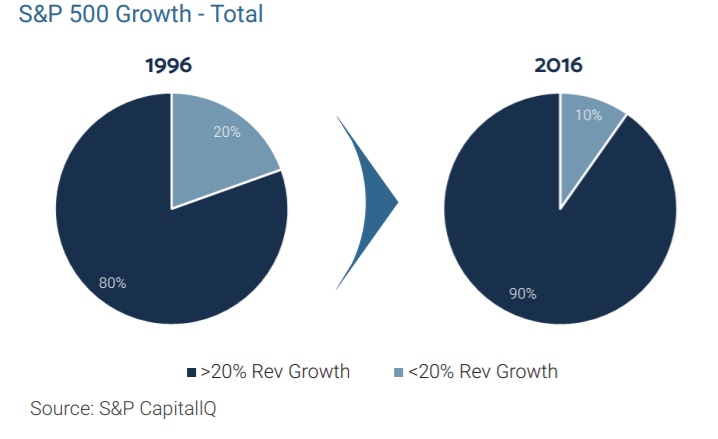

However, this same song has been played before and the chorus goes: “bigger is not better”

As VC firms and investment banks opt for larger market capitalizations, the growth of these companies after IPO has decreased.

Which makes intuitive sense — if you wait to invest into a company until after it’s worth $3B, the likelihood of it growing to become worth $10B is low, because they’ve already squeezed so much juice out of the lemon.

As a result, the IPO market has been described as: “a holding pen for massive, sleepy corporations” [2.5].

How do we prevent this from happening to VC?

If VC wants to continue generating the returns it has in the past, it needs to get out of its scarcity mindset. How?

1. Build a bigger tent

This scarcity mindset impacts how VCs are investing in companies and their own teams.

I recently read that having a scarcity mindset makes people more racist [3].

If this is true, we are seeing it play out in venture both in the types of teams VCs back and the types of people VCs hire/promote.

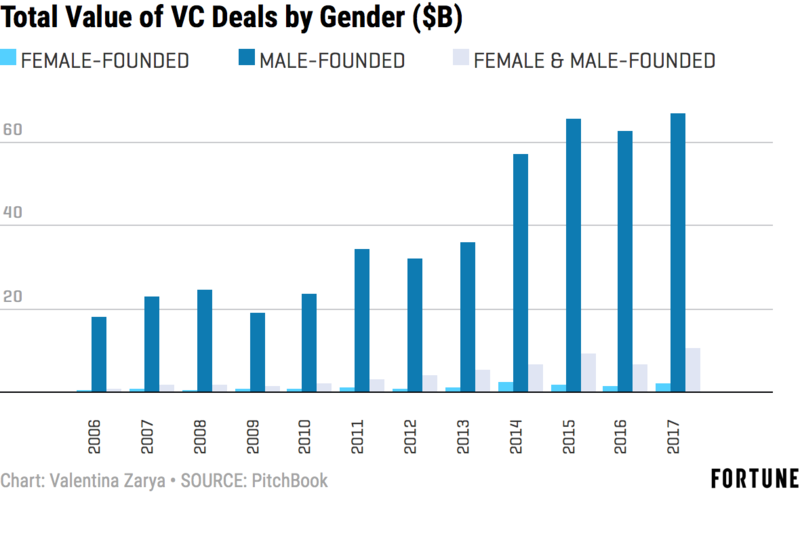

Only 2% of venture capital funding goes to women entrepreneurs, and less than 5% of entrepreneurs backed by venture capital firms are black or Latinx [4].

Venture Capital teams aren’t doing much better. The number of female partners only increased from 2017 to 2018 by 2% and the number of black and latino investors decreased [5].

But does this have to be true? The data shows that there is enough capital to spread around and that if firms were creative, there are enough venture capital jobs to go around as well.

2. Enable Public Access to Early Stage Funds

“The pre-IPO market has become the IPO market of the past, but it’s only available to investors such as venture capital firms, mutual funds and hedge funds able to put up large amounts of money that once were only available through public markets.” [6]

If a pension fund is able to invest a person’s pension into a VC fund, why can’t that person decide to invest into another entity that invests into a VC fund?

Let’s be clear, I am not advocating that individuals should be investing their own retirement dollars into investment firms directly. Instead, I’m thinking of something more in line with Fundrise, but for VC funds. Something that allows the public market to have diversified access to early stage investment firms. Especially as the availability of pensions continue to wade, giving fewer and fewer everyday people access to these early investment opportunities which are driving the largest returns.

3. Act Like We’re the Longest Assetholders (because we are)

Back in its heyday, one of Kleiner Perkins’ biggest investments was a $100K check into Genentech. It turned into $47 billion three decades later [8].

As we continue to invest in the future of a world we can’t even imagine, we are going to have to take risks on ecosystems, people and ideas that are out of this world crazy. We can’t invest in what would work right now, because the point is that just because it works now, doesn’t mean it will work later. Instead, we are choosing to invest in the unknown — into something that might work in the future.

This lens towards investing in weird, crazy ideas has always been a nomenclature of VC, but this hasn’t actually played out. Instead, the industry has decided to rally around big buzzwords every few years. Big data! AI! Cannabis! Instead of taking a longer and more humble view on the fact that the future is unpredictable. And instead of trying to move it in our favor, by overcapitalizing a few “winners”, perhaps we should be open to a world where more people were given a chance at bat and in return we had a more comprehensive stake in an unpredictable world.

“In the United States, for example, “trickle down” economic policies that support tax cuts for the rich with the aim of boosting economic growth and jobs have led to a $2 trillion annual redistribution of wealth from the bottom 99 percent of earners to the top 1 percent over the last 30 years, said Nick Hanauer, a former venture capitalist and now head of Civic Ventures, which aims to drive social change.

If the trend continues, by 2030, the top 1 percent of Americans will earn 37 to 40 percent of the country’s income, with the bottom 50 percent getting just 6 percent, he said.

“That’s not a capitalist market economy anymore,” he warned. “That’s a feudalist system and it scares … me.”” [9]

[1] “7 Habits of Highly Effective People”, Stephen R. Covey

[2] https://blog.greenspringassociates.com/venturecapitalsaccessmyt

[2.5] “The Deregulation of Private Capital and the Decline of the Public Company”, Elisabeth de Fontenay, https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6431&context=faculty_scholarship

[3] https://www.thecut.com/2014/06/scarcity-might-make-people-more-racist.html

[4] https://www.nber.org/papers/w23082.pdf

[5] https://medium.com/allraise/was-2018-the-year-of-the-woman-e2824f513a09

[6] https://www.pantheon.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Shrinking-Public-Markets-Final.pdf

[9] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-democracy-wealth-inequality-idUSKCN0XC1Q2